What does it mean to be a U.S. income taxpayer? Very simply, it means that you are taxable on your worldwide income and gains, even if you don’t live full-time in the U.S. Any U.S. citizen is likely already familiar with this concept (and if they weren’t, perhaps they learned the hard way). In addition, U.S. residents are also subject to worldwide income taxation. Most people are probably already aware that the status of being a permanent resident alien (i.e., having a green card) means you are a U.S. taxpayer; however, even those individuals who are not U.S. citizens and who do not have a green card can be U.S. taxpayers based on the amount of time that they spend in the U.S. in a given year. This concept was perhaps no more in the spotlight than during last year amidst the travel restrictions brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, where individuals not intending to spend large amounts of time in the U.S. were prevented from leaving.1 This article provides a brief refresher of the rules for determining U.S. income tax residency under what is known as the substantial presence test (or the “SPT”).

The SPT in its simplest form can be summed up as follows: If an individual’s days of presence in the U.S. for any year equals or exceeds 183, that individual will be considered a U.S. resident under the SPT. While it appears simple enough, numerous exceptions and nuances abound.

For starters, the test operates not on a single-year basis but on a rolling basis under which days are weighted in order to arrive at the 183 day total. 100% of the days of presence in the current year are counted, 1/3 of the days in the previous year are counted, and 1/6 of the days in the year prior to that are counted. So for someone trying to figure out if he or she will be considered a U.S. income tax resident in 2021, that person would need to analyze their 2021 U.S. day count total, along with their 2020 U.S. day count total (divided by 3), and their 2019 U.S. day count total (divided by 6). Adding these three numbers up, if the sum is 183 or more, the person is a resident under the SPT for the year in question.

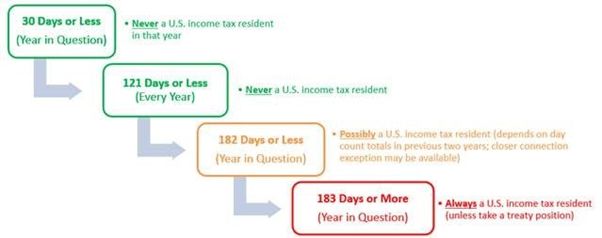

Except that, regardless of the day count total in any previous year, an individual can never be considered a U.S. income tax resident under the SPT for the year in question if such individual is not present in the US for at least 31 days during that year.

All of this sounds convoluted, and for the most part, it is, but because the test is entirely mathematical, there are some guidelines that can help. These guidelines can be thought of in terms of categories. In the first category are those people who, for any given year in question, were present in the U.S. for 121 days or less. These people are in the safe zone and will avoid U.S. resident status under the SPT (indeed, as many practitioners and even quite a few clients themselves know, 121 is often thought of as the ‘magic number’ under the SPT).

In the second category are those people who are present in the U.S. in a given year anywhere from 122 to 182 days. This is the yellow zone. Residency status for these individuals for the year in question will depend in part on their day count totals in the previous two years and the total under the SPT calculation. Assuming, however, that the individual’s 3 year total would otherwise equal or exceed 183 under the SPT, an individual in this zone can nevertheless avoid U.S. resident status if either: (i) the individual qualifies for the closer connection exception; or (ii) the individual qualifies as a resident of a non-U.S. country under the “tie-breaker” provisions of an applicable U.S. income tax treaty.2

In the third category are those people who were present in the U.S. for 183 days or more in a given year. This is the red zone because, for these people, their only hope of avoiding U.S. resident status generally lies in qualifying under the tie-breaker provisions of an applicable income tax treaty. Note, however, that for many clients from Latin America, this option will not be available, as the U.S. currently only has income tax treaties with Mexico and Venezuela.

And as a final bonus category – remember, regardless of the amount of time an individual has been present in the U.S. in the previous two years, an individual who spends 30 days or less in the U.S. in a given year will not be considered a U.S. resident under the SPT for that year (even if the individual was present in the U.S. for 365 days in each of the prior two years).

The following can be used as a visual aid for those individuals present in the U.S. whose days “count” for purposes of the SPT:

The discussion thus far has presupposed that an individual’s days of presence in the U.S. actually “count” for purposes of the SPT. This is not always the case, however, as exceptions apply. Specifically, for a select handful of special categories of people known as “exempt individuals,” days of physical presence in the U.S. are not counted when applying the SPT. These special categories of people are: (i) certain foreign government-related individuals; (ii) teachers or trainees; (iii) students; and (iv) certain professional athletes. Each of these categories has its own requirements and will also depend in part on an individual’s U.S. immigration law status. Further discussion about these rules as it relates to students will be the topic of another post.

Being an “exempt individual” is not the only way to avoid having one’s days count. For certain individuals who become sick while in the U.S., a medical condition exception may be available to exclude days of presence. As another exception, an individual generally does not have to count a day in the U.S. if the person is just in an airport switching flights.

It is also worth noting that for those individuals in the yellow and red zones, in order to avoid classification as a U.S. income tax resident under the SPT, additional steps will need to be taken in the form of U.S. tax filings (e.g., the filing of IRS Form 8840 in order to claim the closer connection exception).

The foregoing discussion should demonstrate just how many nuances there are in applying what seems to be a straightforward test. The consequence of incorrectly applying the rules – taxation of worldwide income and gain – are dire and warrant a close examination of a client’s facts to ensure that he or she is not inadvertently becoming a U.S. taxpayer. Additionally, it is worth noting that the foregoing discussion is relevant only for purposes of determining an individual’s status for U.S. federal income tax purposes. For U.S. federal estate and gift tax purposes, a different concept known as “domicile” is determinative, but here again, that is a discussion best left for a future post.